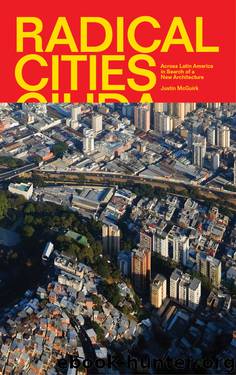

Radical Cities by Justin McGuirk

Author:Justin McGuirk

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Verso Books

23 de Enero

It was not always thus. In the 1950s, the military junta headed by Marcos Pérez Jiménez embarked on a vast programme of investment in the infrastructure of Caracas. Expanding Venezuela’s oil production, the dictatorship poured money into construction projects, using American cities as his model and American expertise to make Caracas the most modern city in Latin America. Jiménez was another dictator fond of bulldozing the barrios. During the 1940s the population of Caracas had doubled, swelling the slums around the periphery. The regime’s response was to forcibly decant the barrio dwellers into a social housing project on a scale that the continent had never seen. It was to be called 2 de Diciembre, the date in 1952 when Jiménez seized power. And in just three years, from 1955 to 1958, the estate was ready to house 60,000 people in one fell swoop. It was more than double the size of Pruitt-Igoe in St Louis, which had also just been completed, and which would become infamous when it was demolished twenty years later.

It is one of the ironies of Latin America that military dictators were so much more effective at building social housing than their democratically elected counterparts. Of course, operating by diktat makes it easier to divert government funds, steamroll opposition and bypass due process. But it was also a function of the historical moment: the dictatorships held sway during a period – from the 1950s in Venezuela to the early 1980s in Brazil – when mass housing schemes were still seen as the answer and had not yet been discredited. As we saw in Argentina, the dictatorships were also ruthless at using housebuilding to buy loyalty, especially among the military. Still, it is counter-intuitive that a regime as corrupt and despised as Jiménez’s should have produced what remains ostensibly the most ambitious urban social legacy of any Venezuelan government. When he was finally ousted in 1957, the estate was renamed 23 de Enero – 23 January, the date of democracy’s return.

The architect who designed 23 de Enero was Carlos Raúl Villanueva. A graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and a disciple of Le Corbusier, Villanueva was Venezuela’s most prominent architect. He had recently completed the campus for the Universidad Central de Venezuela, one of the most gracious modernist campuses in the world. And now, with funding from the Banco Obrero, he had the chance to build his tour de force. He conceived of 23 de Enero as thirty-eight superbloques supplemented by dozens of medium-sized blocks, providing over 9,000 units. These were to be scattered evenly across a terraced hillside to the west of Caracas, with acres of green space in between. The very picture of modernist utopia, this was paternalistic politics as spectacle.

However, in the confusion after the overthrow of Jiménez, and before it was even completed, 23 was squatted by an estimated 4,000 families. This rather set the tone for how the estate was occupied over the coming years. With the Banco Obrero losing out on so much rental income, 23 was never properly administered or maintained.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11846)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9006)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5202)

Paper Towns by Green John(5196)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5104)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5065)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4317)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4058)

Never by Ken Follett(3963)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3867)

Goodbye Paradise(3813)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3417)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3405)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3403)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3351)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3312)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3280)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3132)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(3088)